The Path for Greater Israel: Post-9/11 Wars, Regional Collapse, and the Road Ahead

From Baghdad to Damascus, decades of war has cleared the path for Israeli expansion, but the region's resistance may not be finished quite yet.

In the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, a blatantly obvious false flag operation, the United States and its allies launched a series of military interventions across the Middle East that would irrevocably alter the region’s geopolitical landscape. While these wars were justified under the banners of counterterrorism and spreading democracy, their long-term effect has been the systematic dismantling of states that once posed a strategic counterweight to Israeli regional dominance. From the disintegration of Iraq to the decade-long attrition of Syria’s Assad Regime, Western military campaigns have cleared a path for what some describe as the realization of the “Greater Israel” project, a concept rooted in early Zionist thought and geopolitical scheming (Herzl, 1897; Yinon, 1982).1 With the recent collapse of the Bashar al-Assad regime, a long-standing pillar of the “Axis of Resistance”, the Middle East stands at a critical point from which many interesting developments are soon to follow.

I. The Neocon-Zionist Alliance: Shaping the War on Terror

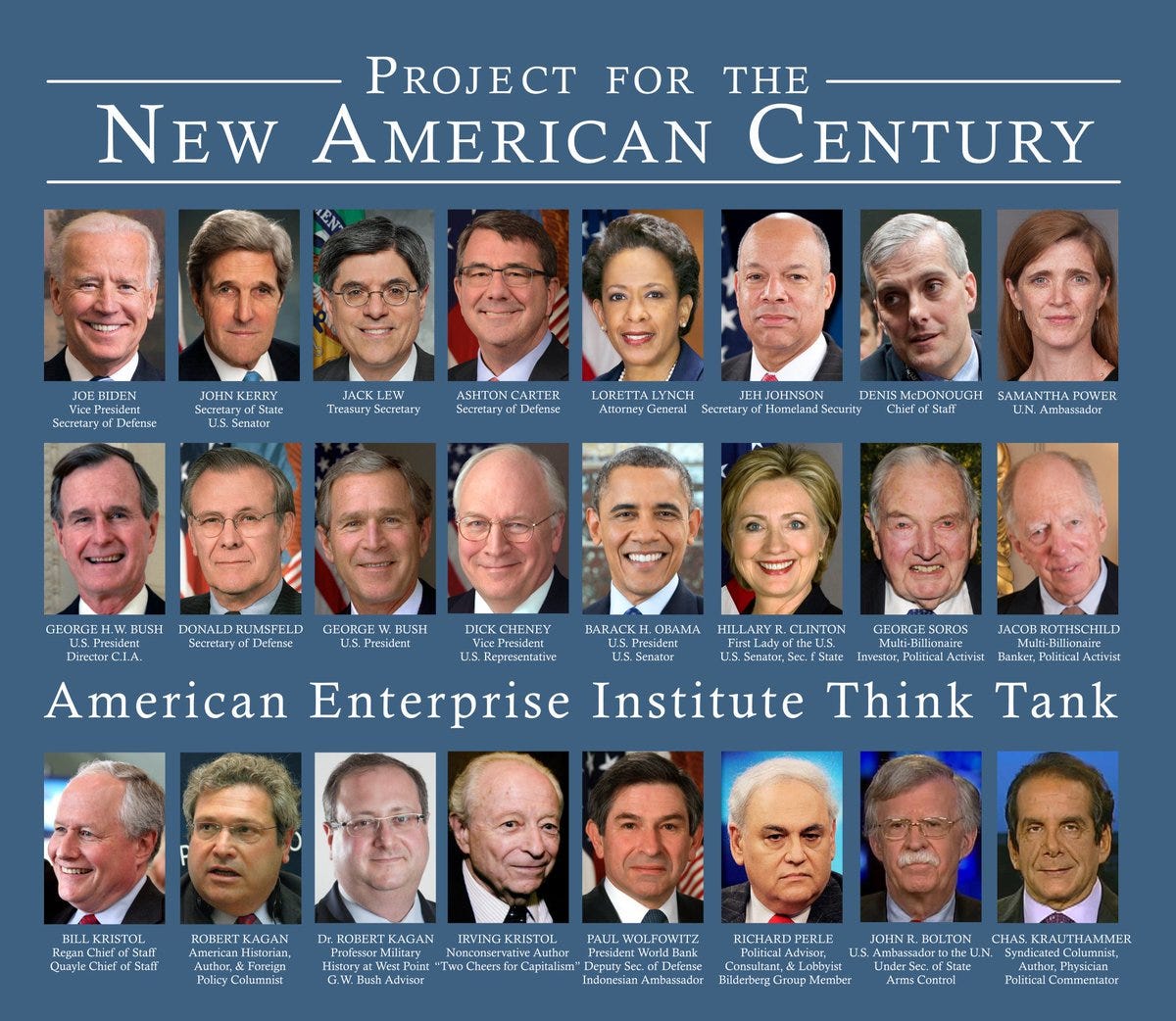

To truly understand the past three decades of Middle East geopolitical chaos, it is essential to understand the neoconservative movement in the United States. In the immediate aftermath of 9/11, the foreign policy establishment in Washington quickly coalesced around a neoconservative vision of reshaping the Middle East through military intervention. Many of the key figures driving this agenda—Paul Wolfowitz, Richard Perle, Douglas Feith, and Elliot Abrams among them— were not only staunch neocons but also outspoken supporters of Israel; not surprisingly, since they are all Jewish. Their ideological commitment to spreading “liberal democracy” was matched or outmatched by their desire to remove regimes seen as threats to U.S. and Israeli interests alike.

This ideological overlap was most clearly articulated in a now-infamous 1996 policy paper titled A Clean Break: A New Strategy for Securing the Realm, written for then-Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. This paper, authored by several future Bush administration officials, including Feith and Perle, explicitly called for the removal of Saddam Hussein and the rollback of Syria’s influence in Lebanon as key components of Israel’s regional dominance (Institute for Advanced Strategic and Political Studies, 1996).2

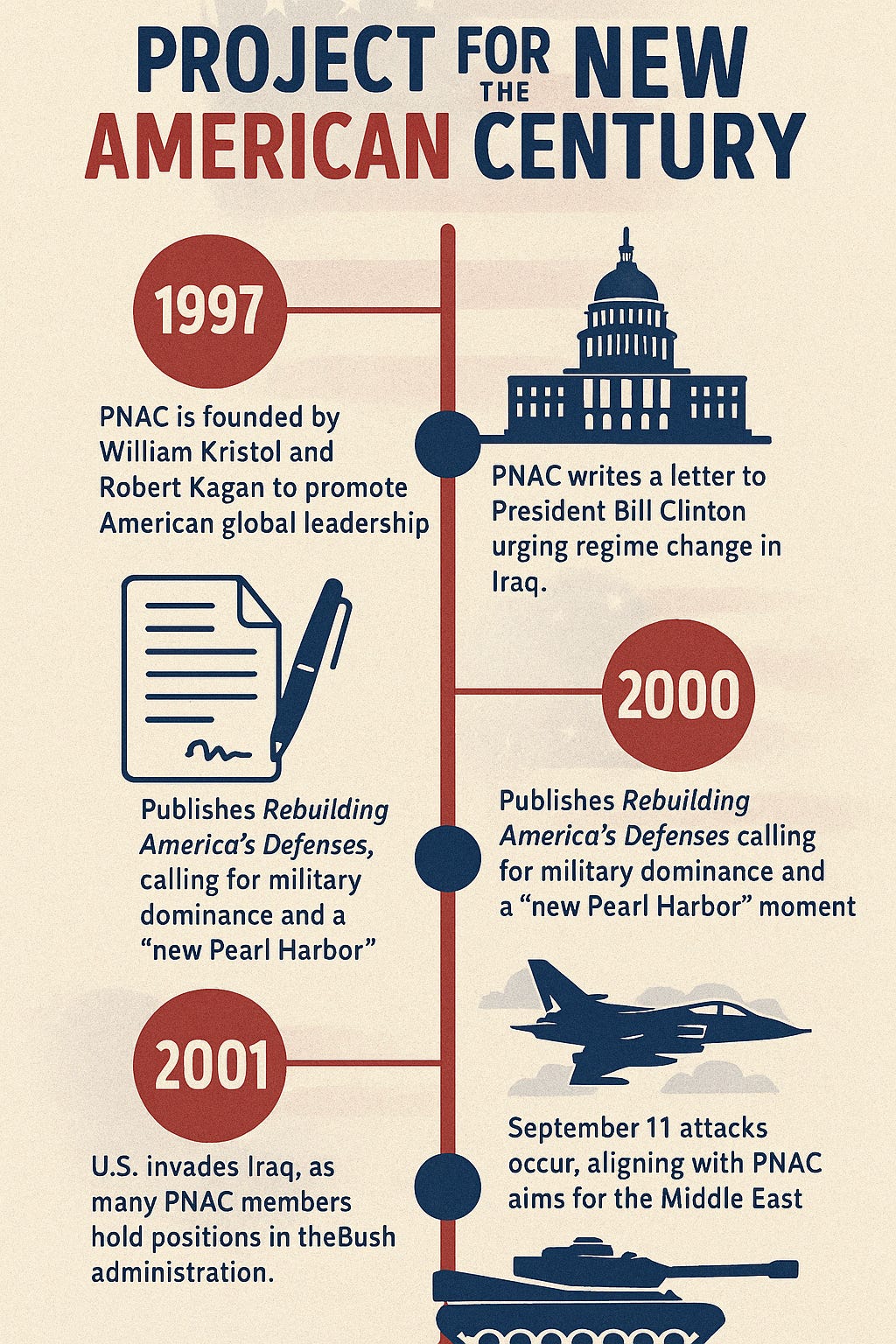

Similarly, the Project for the New American Century (PNAC), a neoconservative think tank in favor of Israeli interests established in the late 1990s, laid the intellectual foundation for the Iraq War. In its 2000 report, titled Rebuilding America’s Defenses, PNAC emphasized the need for American military preeminence and identified Iraq, Iran, and Syria as strategic threats to be dealt with. The report openly admitted that these transformations would be politically difficult to achieve “absent some catastrophic and atalyzing event—like a new Pearl Harbor” (PNAC, 2000).3

That new “Pearl Harbor” came with 9/11. Within months, the Bush administration had not only invaded Afghanistan but begun building the case for war in Iraq—a country that had absolutely zero role in the attacks but had been a target of Israeli security planners. The Iraq War, which dismantled the most formidable Arab military power in the Middle East, was hailed by many in the Israeli security establishment as a major achievement for its interests.

So now this all raises several critical questions: Were these wars waged primarily for American interests, or were they influenced and pushed for by Zionists embedded in the U.S. government to aid in Israel’s geopolitical conquest of the region? We shall delve deeper into this throughout the article.

II. Iraq: The First Domino

The 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq was sold to the world as a necessary response to Saddam Hussein’s dictatorial regime that supposedly had weapons of mass destruction and ties to Al-Qaeda. Both claims were later debunked, but the war went forward with devastating consequences for the country and the broader region. What followed was not the birth of a liberal democracy but rather the death of a functioning Arab state. The removal of Saddam, one of the last secular Arab nationalists capable of projecting regional power, was not only a disaster for Iraq but a strategic victory for Israel.

Saddam Hussein had long been a vocal opponent of Israel, famously launching missiles at Tel-Aviv during the 1991 Gulf War and offering financial compensation to families of Palestinian suicide bombers during the Second Intifada. With his regime gone, a significant military and ideological obstacle to Israeli hegemony was eliminated. As Israeli political analyst Aluf Benn noted in Haaretz, “Saddam’s ouster removed a regional rival that had challenged Israel’s regional dominance and threatened its security” (Benn, 2003).4

Many in the Israeli security establishment quietly welcomed the war. While official statements were cautious, former Prime Minister Ariel Sharon’s advisor, Raanan Gissin, told the New York Times in 2003 that “the day after" Saddam’s fall would be a safer day for Israel (NYT, 2003). Benjamin Netanyahu, then a private citizen, told the U.S. Congress in 2002 that if “you take out Saddam, I guarantee that it will have enormous positive reverberations on the region (Netanyahu, 2002).5 In addition, he blatantly lied to the American public, stating to the U.S. Congress that Saddam Hussein was developing nuclear weapons.

“There is no question whatsoever that Saddam is seeking, is working, is advancing towards the development of nuclear weapons… Once Saddam has nuclear weapons, the terror network will have nuclear weapons.”

These “positive reverberations” that Netanyahu spoke of would take the form of a sectarian collapse that spread like wildfire. Iraq descended into years of chaos, with Sunni, Shi’a, and Kurdish factions vying for control. The ensuing power vacuum gave rise to ISIS, whose violent campaigns not only fractured Iraq but spread to neighboring Syria, accelerating the nation’s civil war. The destabilization of Iraq as a unified state had been planned for a long time by Israeli policy planners. Oded Yinon’s 1982 policy paper had called for the fragmentation of Iraq into Sunni, Shi’a, and Kurdish territories as a means of neutralizing a potential rival (Yinon, 1982).6

Rather than stabilizing the region, the war in Iraq fulfilled the very blueprint articulated decades earlier: dismantle strong Arab states, ignite sectarian divisions, and create a geopolitical landscape in which Israel’s security would no longer be challenged by any of its neighbors.

II. Syria: The Protracted War and Assad’s Fall

For over a decade, Bashar al-Assad was seen as the immovable pillar of the so-called “Axis of Resistance”— a bloc that included Iran, Hezbollah, and at one point, Iraq. But the Syrian Uprising in 2011, catalyzed by the Arab Spring, marked the start of a long war of attrition. Though Assad clung to power for years with the backing of Iran, Russia, and Hezbollah, his regime ultimately fell in December 2024 during a massive rebel offensive supported by the Gulf States and tacitly greenlit by the West (Al Jazeera, 2024).7

The implications of Assad’s fall are seismic. Not only does it sever the land corridor that connected Iran to Hezbollah in Lebanon, it also removes one of the last remaining Arab regimes that was overtly hostile to Israel. For Tel-Aviv, Assad’s removal was just another chess move in their grand strategy to establish a hegemony in the Middle East. Throughout the Syrian conflict, Israel conducted hundreds of airstrikes on Iranian and Hezbollah-linked positions inside Syria, justifying them as preemptive defense (Washington Institute, 2021).8 But these actions were part of a broader doctrine to weaken Iran’s regional axis by bleeding Syria into fragmentation.

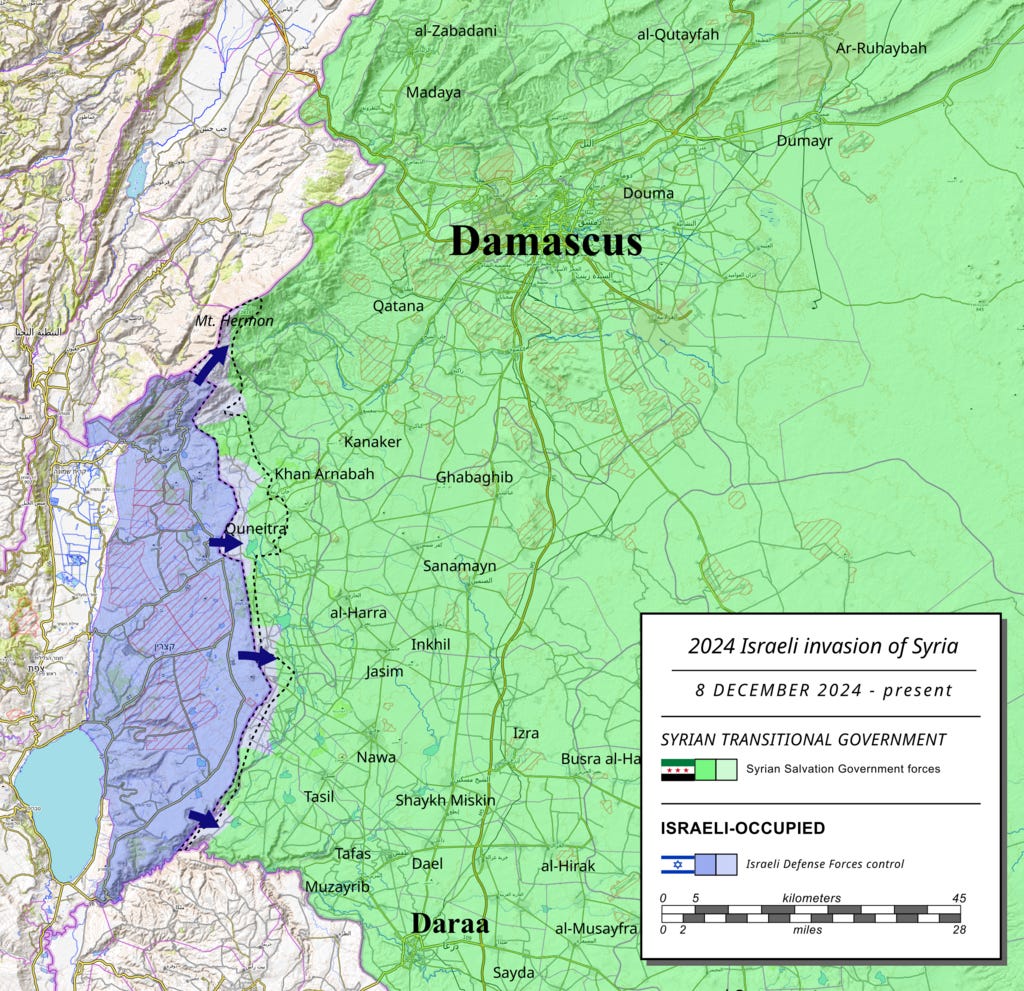

Following Assad’s fall, Israel has moved quickly to consolidate its position in the occupied Golan Heights—a region it captured in 1967 and effectively annexed in 1981, illegal under international law. With Damascus in chaos and no strong Syrian state left to contest the occupation, Israel has accelerated infrastructure development in the Golan and opened new settlements under the guise of security and stability. The region, rich in water resources and of high strategic elevation, is now becoming a permanent Israeli frontier, one no longer in diplomatic discussion but of de facto rule (UN OCHA, 2024).9

Some Israeli officials have even hinted at expanding their military presence into southern Syria, citing the need to “prevent Iranian entrenchment” and ensure “defensive depth”. What was once a contested borderland is now becoming another forward operating base to support the Greater Israel vision.

Assad’s regime, while autocratic and brutal, had long served as a buffer against unchecked Israeli expansion. It supported Palestinian factions, resisted normalization, and helped arm Hezbollah. With Assad gone, and no coherent Syrian state likely to emerge for years the country is now expected to undergo sectarian and ethnic fragmentation, echoing the blueprint outlined in Oded Yinon’s 1982 policy paper, which advocated breaking Syria into smaller, more manageable pieces as a way to secure Israeli hegemony (Yinon, 1982).

The current Syrian president, Ahmed al-Sharaa, who was formerly the leader of the jihadist group Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), has done nothing to resist Israeli expansion into Syria. On the contrary, his administration has been marked by tacit cooperation or, at the very least, passive allowance of Israeli military operations within Syria’s borders.

Al-Sharaa’s silence as the IDF launched its March 2025 ground invasion into the Quneitra Governorate speaks volumes. The once fiercely defiant Syria has been reduced to a broken state ruled by a former Jihadist leader with no ideological opposition to Israel, only opportunistic rule. Compounding this, newly declassified statements by former IDF Chief of Staff Gadi Eisenkot revealed that Israel had supplied weapons to Syrian rebel groups for years, long denied but now confirmed. Eisenkot admitted these arms shipments were designed to create buffer zones and counter Iranian presence (Times of Israel, 2019).10 In other words, Israel had been actively shaping the post-Assad order long before Assad even fell.

III. Iran: The Final Bastion of Resistance

With Iraq shattered and Syria fractured, Iran stands as the last formidable power in the Axis of Resistance. But for decades, it has also been the primary target of Israeli strategic anxiety. Ever since the 1979 Iranian Revolution that brought in an anti-Zionist theocracy to power, successive Israeli governments have viewed Iran as a major geopolitical rival and an existential threat. The rhetoric around Iran’s acquisition of nuclear weapons has only intensified that fear.

Israel’s acts of aggression against Iran have unfolded on several fronts. Through covert assassinations of nuclear scientists, cyberattacks like Stuxnet, and repeated airstrikes on Iranian proxies in Syria and Iraq, Israel has long waged a shadow war designed to keep their enemy contained (Atlantic Council, 2024).11 As early as the 1990s, Israeli officials have lobbied the United States to intervene militarily in Iran to stop their nuclear ambitions (Haaretz, 2023).12 In recent years, their lobbying has only intensified. Following the U.S. withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal (JCPOA) in 2018 under the Trump administration, Israel has aggressively pushed for what it calls a “military solution” to Iran’s nuclear program.

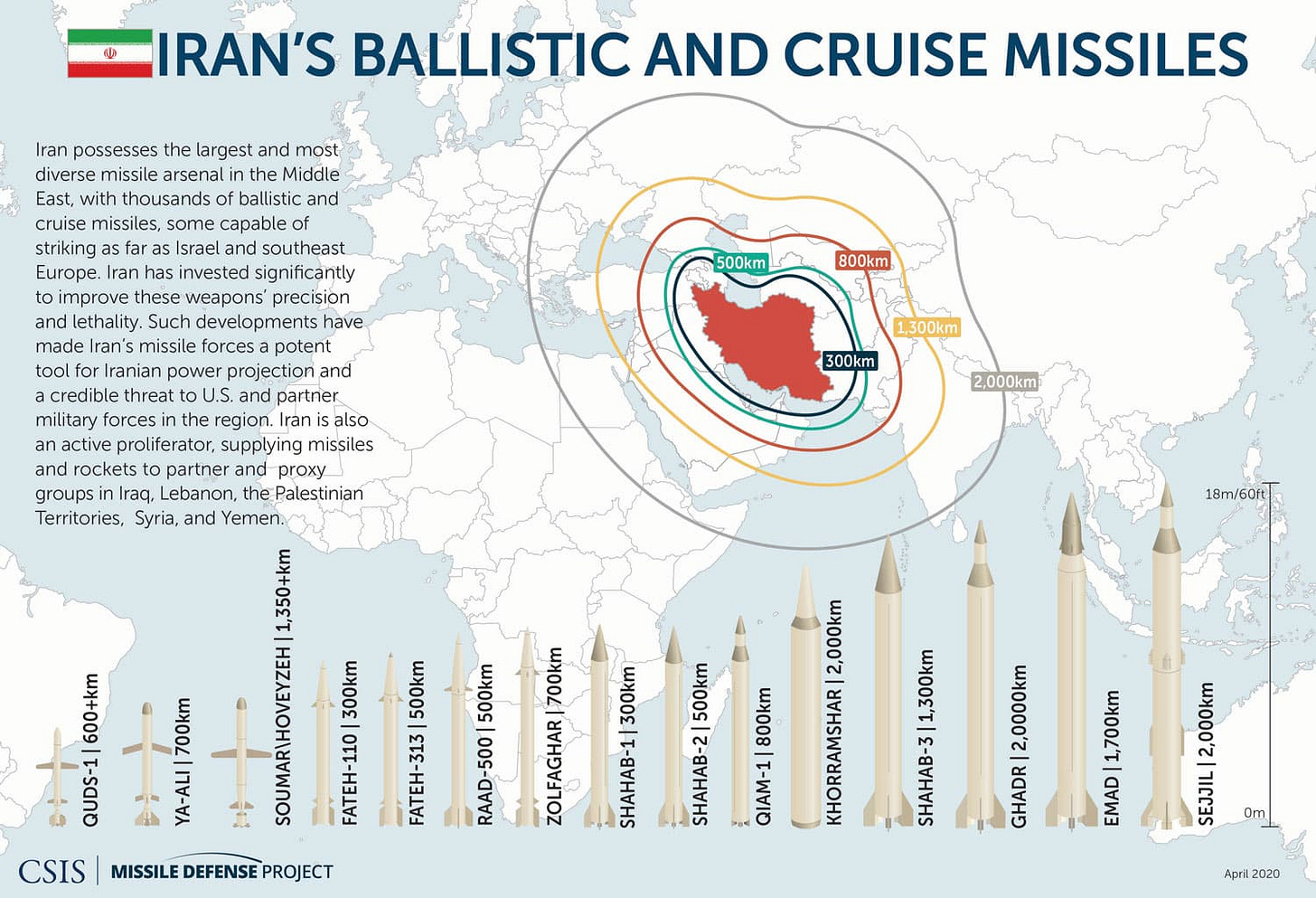

In 2025, with Assad gone and Hezbollah geographically cut off, along with their leader Hassan Nasrallah being killed in an Israeli airstrike last September, Israel’s focus has shifted almost entirely to preparing the battlefield confrontation with Iran itself. Aerial drills simulating long-range bombing runs, deployment of missile defense systems, and public discussions of a preemptive strike all point to the same conclusion: war with Iran is no longer hypothetical, but rather an inevitable reality.

However, beneath all this rhetoric is a deeper concern: Iran’s missile arsenal. Over the past two decades, Iran has built one of the largest and most advanced missile programs in the region, including medium-range ballistic missiles like the Shahab-3 and Emad, and highly accurate cruise missiles like the Soumar and Paveh. These weapons can reach deep into Israeli territory, strike U.S. bases across the Gulf, and potentially overwhelm even advanced missile defense systems like Iron Dome or David’s Sling (Reuters, 2024).13

The presence of this arsenal dramatically alters the geopolitical calculus. A direct attack on Iran could trigger a massive retaliation, not only from Tehran itself but through its network of allied militias across the region. Israeli defense analysts admit that a full-scale war with Iran would be qualitatively different than their previous engagements with Hamas or Hezbollah. It would involve a regional conflagration, with major infrastructure, oil routes, and refineries, and population centers under threat across the Gulf and the Levant (BBC, 2025).14

For Israel, the collapse of Iran would mark the final act in a long strategy of regional transformation: no Arab state left standing, no supply routes to Hezbollah, no ideological challenges to its nuclear-armed status quo. But for the region, it would mean all-out war—one that would certainly mean severe devastation for all actors involved.

IV. What Comes Next

Two decades after the 9/11 attacks, the geopolitical map of the Middle East has been redrawn, not by coincidence but by redesign. The collapse of Iraq, the dismemberment of Syria, and the looming confrontation with Iran all align with a broader pattern: the systematic removal of states that once challenged Israeli military and territorial ambitions.

What was once theorized in strategy papers or whispered in neoconservative think tanks has in many ways materialized. Yet even amid this apparent triumph, resistance persists—not from capitals, but from decentralized actors like the Houthis, who now carry the torch of defiance in a blood-stained region.

Whether the vision for Greater Israel becomes a reality in the upcoming decades will depend on how today’s regional dynamics continue to unfold.

References

Herzl, Theodor. The Diaries of Theodor Herzl (1897); Yinon, Oded. A Strategy for Israel in the 1980s (Kivunim, 1982)

Institute for Advanced Strategic and Political Studies. A Clean Break: A New Strategy for Securing the Realm, 1996.

Project for the New American Century (PNAC). Rebuilding America’s Defenses: Strategy, Forces and Resources for a New Century, 2000.

Benn, Aluf. “Saddam’s Fall a Boon for Israel.” Haaretz, 2003.

Netanyahu, Benjamin. Testimony to U.S. House Committee on Government Reform, Sept. 2002.

Yinon, Oded. A Strategy for Israel in the 1980s, Kivunim, 1982.

Al Jazeera, “End of Assad: Rebel Forces Enter Damascus,” 2024.

Washington Institute for Near East Policy, “Israel’s Covert War in Syria,” 2021.

UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), “Israel’s Expansion in the Golan Post-Assad,” 2024.

Times of Israel, “IDF chief finally acknowledges that Israel supplied weapons to Syrian rebels,” 2019.

Atlantic Council (2024). “The Endgame in Iran: What a U.S.-Israel War Would Look Like

Haaretz (2023). “Netanyahu Revives Push for Iran War.”

Reuters (2024). “IDF Simulates Long-Range Strikes on Iranian Targets.”

BBC (2025). “What Happens if Israel Attacks Iran?”